The times I'm most engaged as a writer is when I'm writing dialogue.I write slowly by nature, but with dialogue, I can't write fast enough! I usually skip the dialogue tags and action beats between the lines, just trying to stay on top of the words my characters are spewing back and forth to each other. I often know what they say in the middle or at the end of a conversation, and I bounce back and forth trying to capture everything. Once I finally get their words out, I go back and plug in the necessary tags and beats.

While I don't pretend to be the know-it-all master of dialogue, I can tell you some of my tried-and-true tricks.

I'd say good dialogue comes down to two rules: it needs to sound natural and it needs to be compact for the purposes of tight fiction (which is not how people speak in real life). The two rules oppose each other, and it's the writers job to strike the right balance.

Natural Dialogue

When I was little girl, my siblings and I would record our voices onto audio cassette tapes. Then in my early teens my dad bought a video camera. So in some format or another, I was constantly recording improvisational scenes. If you haven't tried improv acting before, I'd highly recommend it. Even if you'd rather be an observer, you can attend local improv comedy troupe shows and LISTEN, LISTEN, LISTEN to the dialogue that comes naturally and on-the-spot from these actors. (Listening to real conversational speech is beneficial as well, but be careful because "real people" don't speak compactly...more on that later.)

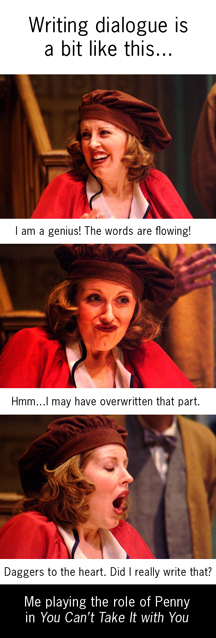

In high school I began acting in plays and did so throughout college and beyond. Because plays are 95% dialogue, I was forced to analyze, line by line, scene by scene, what I was required to say and how to make it work. I had to find the objective, motivation and tactics for my character. I had to know what I was really saying between the lines. And there was nothing worse than trying to act well while delivering a badly written line. I constantly considered whether dialogue (especially written by amateur playwrights) was something my character would really say--if it sounded believable, natural.

Then throughout high school I wrote in volumes upon volumes of journals. My average was ten pages a day, and on really good days, I would write up to fifty pages (and these were large-paged journals, not tiny pocket-sized ones). I wasn't thinking dialogue, dialogue, dialogue as I wrote these entries, but that's what they mostly were comprised of. Somehow I recalled conversations from the day, and I recorded them in my journal, not in a summarizing fashion, but moment for moment, word for word--"in-scene." I would skip to the part of the conversation that got interesting and start there (and I'd stop writing before the conversation got dull again). Which brings us to the next point in writing good dialogue:

Compressed Dialogue

It would sound natural (but would be painstakingly boring) if we wrote dialogue just as it is in real life. It would read like this:

"Hey."

"Hey."

"What's up?"

"Not much."

"Nice day."

"Yeah. Might rain later."

"Mmmm."

"So..."

"Yeah?"

This is small talk. Not much tension or conflict. The best dialogue--even between characters who like each other or are on the same side--must have conflict. So here is where we bend the law of natural dialogue to include only the most interesting parts, which again, must have conflict. I have to now go back to the dialogue I wrote where I let my characters endlessly banter and go off on tangents and trim it down to fit the purpose of the scene. And if my character felt the need to make some big speech (and you can only get away with so many of these), I need to liposuction that as well, and then break it up with beats, interiority, and reactions from the other character(s).

Check Your Dialogue

The most important thing you can do to test the quality of your dialogue is to read it aloud--or even better, have someone else read it aloud to you. Become actors and stage the scene you wrote. As you speak aloud, see where you or your friend stumble on the wording, or where your ears--and not your eyes--tell you something is wrong. Additionally, make sure your characters have different voices, patterns of speech, etc. And make sure the dialogue mechanics are helping, not hindering, the conversation of your characters. Get rid of dialogue tags when you can--but not all, as not to exhaust your reader. If you use beats in place of a dialogue tag, and in where it's otherwise unclear who is speaking, it's best to write the action beat before that character starts talking. For example:

"Are you going to tell me what happened last night?" Jane said.

Michael fiddled with his shoelaces, not meeting her eyes. "What's for dinner?"

The above example also works for misdirecting the conversation, which is another great dialogue tool. Rather than have your characters speak plainly back and forth to each other, it's nice when they try to change subjects, interrupt each other, trail off, beat around the bush, speak in fragmented sentences, and answer a question with a question. All these tactics add tension, conflict and believability to the scene.

Some other quick reminders:

- Make sure your stick to "said" as much as possible in your dialogue tags.

- Don't use physical impossibilities for speaker attributions. (A character doesn't "laugh" or "grimace" a line of speech. They SAY it. So none of this: "Let's have a picnic," Teresa smiled.)

- Paragraph your dialogue (a new paragraph for each person speaking). For the most part, this rule applies for character reactions too. So if one character is speaking and the other character reacts rather than says anything back, place that reaction in a separate paragraph, as if it were a line of dialogue.

- Don't explain in your interiority or action beats what is apparent by the dialogue alone. Interiority is best used when it's revealing thoughts that are in opposition to the dialogue--or at least a completely different line of thought.

- Get rid of adverbs in dialogue tags (he said lovingly) unless they actually modify the verb "said" (quietly, softly and clearly are okay, if you really need them).

- Beware of melodrama in dialogue. Hopefully you can identify this by reading your dialogue aloud. Then make sure your scene isn't all at the same pitch; make sure it builds into a tense moment and there's contrast within the scene. Then compare all your scenes and make sure there is an arc to them--that they're not all at the same emotional intensity.

- Beware of exposition/back story in dialogue. This is okay, but only if it is something the characters would naturally say to each other, and not just a device for the author to divulge necessary information to the reader.

- Don't spell out dialects or accents in language. You CAN use language improperly or irregularly, though. (Like, "You don't got no business talking to me" if a character isn't well educated, or "Please to tell me what you mean" if a character is a foreigner.)

These are all good things to remember. I always get annoyed when people write something like, ""That's awesome," Anna smiled." No. Anna doesn't "smile" those words. She "says" them. I think oftentimes people mean to write, ""That's awesome." Anna smiled." Which works. But the period vs. the comma makes all the difference.

ReplyDeleteGreat post!

Great post on dialogue. Loved the pics of you playing Penny.

ReplyDelete"You're awesome and I love this post," said Jason.

ReplyDeleteFilled with great Yoda-like knowledge, you are. Nice post, Katie. And even better pictures :)

ReplyDelete